Now, flat on my back yards away from the Pacific Crest Trail in the John Muir Wilderness, the reality of my isolation has set in. It is a five-hour horseback ride from our camp in Cascade Valley to the nearest telephone. A hardy backpacker might come this way or the occasional horse tour company, but they have all settled into their respective camps for the night. Cell phone transmissions don’t travel through the granite walls that John loved so well, and something inside my body is terribly wrong.

My wrangler guides are busy chopping wood and are too far away to hear or see me. I comfort myself, while waiting for the blue dome above to stand still, by revisiting the day. We headed for the trail to Iva Belle Hot Springs early this morning. The trail took us over a small rise into a land filled with tall trees heavy with dew diamonds. We slipped silently on needle duff through the woodland like Indians on a hunting march. Mist rose from the forest floor warmed by the morning sun. I listened to the chirp of the mountain chickadees and the rush of the wind through the towering pines. We emerged from the forest to a clearing overlooking Fish Creek.

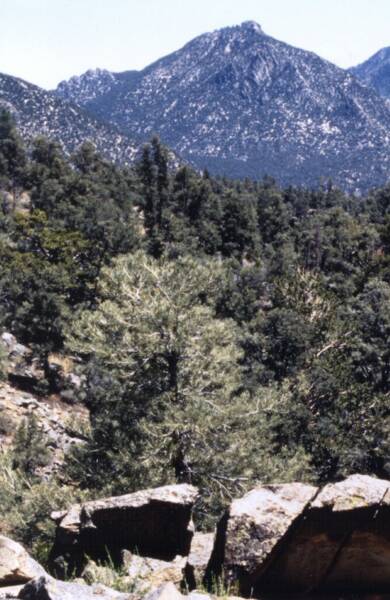

We ambled beside the creek, cascading down boulders the size of boxcars, for a couple of hours. I scanned the deep pools and crevices of the creek trying to find the water ouzel, a clever little bird that dives beneath the water looking for tidbits, that kept John Muir amused for hours. The wrangler’s bottom rocked back and forth in the saddle, while he rhythmically swatted his horse with a quirt, humming a cowboy tune. He made a hairpin turn up the mountain, taking us on a trail that snaked toward the sun. The narrow, boulder-strewn switchback called for the nerves of a bullfighter and the strength of a mule. I was aboard Judy, an unflappable mountain-horse, who casually snagged purple lupine on the side of the trail, never noticing the gorge below. I trusted her sure-footedness and pushed visions of a rider and horse rocketing down the growing chasm from my mind.

Iva Belle Hot Springs rests in a sheltered valley surrounded by rugged peaks. A circle of rocks forms a pool with a pipe jutting out of a boulder, delivering steaming water into a frothy brew. We tore off our clothes, revealing swimsuits and white legs, then jumped into the pool, letting the water melt away the ache of saddle sore muscles. When I reached parboil, I sprawled on a hot boulder, like a marmot, to dry in the warm sun. A cool breeze licked across my wet skin. I sank into the strength of rock, consciously absorbing the essence of Iva Belle imagining that I’d joined John in his reveries.

My recollections of the day were cut short when the sun dropped behind the crest, leaving me chilled. I had to get back to camp before nightfall. I couldn’t wait for someone to stumble upon me. I rolled over on my left side, trying to stand. I could rise, but not without mind-bending pain. I hugged my body, trying to hold my ribs in place, and staggered to the edge of camp. When I could see the wranglers, I called for help and curled back to the ground. They dropped their axes and came running.

“Looks like she bruised her ribs,” I heard Jason, the head wrangler, say. “Don’t move. You don’t want to puncture a lung,” Linda, our cook, said. Her voice seemed far away, even though she was kneeling over me, staring intently into my eyes.

Neither of the wranglers, Linda, nor the two girls on the trip with me, had any medical training. After a brief inventory, it was determined that our entire pharmaceutical arsenal consisted of one Tylenol PM.

Jason, a big, barrel-chested young man, came down on his knee to tell me, “It’s up to you to assess your situation.”

He looked innocent, sweet and scared. As I gazed into his pale blue eyes buried deep in his full-moon face, I felt terminally stupid, helpless and terrified.

“If you want a helicopter, we have to send Shane out right now, before nightfall,” he said.

“How much does a helicopter cost?” I asked.

“It could be a couple a thousand. I don’t really know.”

I scribbled authorization for him to request a helicopter airlift on a piece of brown paper bag. Shane hopped on his already tired horse and rode for help.

Once back in my tent, I tried to get comfortable but was tormented by jolts of stabbing pain. Linda, an ex-grand prix jumper, knew a lot about injuries.

“You got rolling ribs,” she informed me.

My ribs were shifting inside their cartilage casement. About every twenty minutes, I felt, and heard, my bones moving within my body, accompanied by a shaft of stunning pain that made me groan. The muscles in my right shoulder, along my chest, went into spasm, and I couldn’t lift my arm.

Through my tent flap, I saw stars sprinkled across ink black heavens. I heard the crackle of a blazing campfire and the voices of the girls and occasional laughter at a punchline. I was startled out of my misery when Jason lifted the flap of my tent, blocking the starlight with his moonbeam face.

“All you’re missin’ out here is about a billion mosquitoes,” he said.

“Just lucky, I guess,” I said.

Long after the laughter stopped and the rest of the camp settled into separate slumbers, I stared into the dark. Placing fingertips on the inner edge of my rib cage, I breathed deep into the pain, exhaling it from my body. I lay awake until the still gray dawn crept outside my tent flap. It seemed days before I heard the camp stir and the crack of the morning fire. I tested my arm and found I could raise my arm up and down. I attempted to rise, rolling over on my side. I was able to crawl out of my tent on hands and knees. I stood on wobbly knees and hugged my rib cage. It wasn’t worth it. I quickly went back to the ground, and rolled onto my back.

By 10:30 AM, the sun was high, but there was no helicopter. I lay face up, warming in the morning sun, surveying the sky.

Jason’s head blocked my view with his straw Stetson.

“We’re going to have to leave by eleven. I’ve got to get the girls back. We don’t have enough feed and supplies to stay,” he said.

“What’s going to happen to me if the helicopter doesn’t come?”

“I’m leaving Linda and a mule and some supplies with you.”

How long would I be laying on this rock? How long would it take for ribs to heal well enough for me to ride? How much food do we have? I wondered. John Muir survived on biscuits and tea, but I was used to three squares a day. The girls stopped saddling their mounts when we heard the thwank, thwank, thwank of helicopter blades overhead. They ran to a prominent rock and swirled their jackets in the air, trying to get the chopper’s attention. The pilot saw us, but instead of landing, circled several times, then left.

“They can’t find a place to land,” Jason said.

“What does that mean?” I asked.

“It means I don’t think they are going to be able to help,” he said. “I’ll have to come back for you after I get the girls down the mountain.”

“Safe journey,” I said, waving goodbye. Even though Linda was to remain with me, I felt intensely helpless and alone. After about a half hour of contemplating a fate I didn’t believe I deserved, three strange male faces blocked the sun. I’m hallucinating alien beings coming to my rescue. The youngest man, about 30, with close-cropped auburn hair and a shock of brown freckles across his nose, in an official looking uniform, dropped to his knees beside me. He lifted my sweatshirt, and felt my body with knowing hands, looking for injury.

“Does that hurt?”

“Yes.” I blubbered.

Tears of relief welled. I choked back sobs, while he continued his investigation. He lifted me slightly, feeling along my spine, up into my neck.

“Put a brace on her,” he instructed his men.

They slipped a soft cuff around my neck, to hold my head in place. Satisfied with his inspection, he leaned back on one knee.

“Looks like you have broken a couple of ribs, but I don’t think you punctured your lung.”

The men lifted me onto a gurney and carried me to the helicopter waiting in a meadow about a half-mile away. Once inside the chopper, the enormous rotating blades lifted us off the mountain. The medic wrapped a plastic band around my arm to check my pulse.

Safe on the floor of the helicopter cockpit, I asked casually, “How much is this going to cost?”

“Nothin,’” the medic grinned. “This one’s on the Navy. I’d just be sittin’ at my desk doin’ paperwork, if we didn’t get this call.”

My blood pressure dropped with the news. I drifted off to comatose comforted by visions of the trail to Iva Belle meandering beside Fisk Creek. I searched for the water ouzel in the icy stream fed by glacier cirques nestled in granite peaks John had loved so well. One day I will return to feel the teasing breeze rippling the water and find the little bird I know is hiding there.